Indice

Abstract. The paper describes the formation process of the domestic icon – one of the most important religious and ritual objects of the Ukrainian peasantry. Its roots date back to the period of Kyivan Rus’, and its prosperity – to the nineteenth century. The author draws attention to the evolution of tradition and various forms of manifestations throughout Ukraine.

Keywords: domestic icon, Ukraine, everyday life, tradition.

It is not clear when the icons first

appeared on the walls of Ukrainian homes, however, it is a well-known

ancient custom that has been practiced in different countries,

regardless of religion [Sherotsky 1913].

The history of domestic icon is associated with the beginning and end stages of the classic iconography development period. During the birth of Christianity, the icon was an object of personal use. With the evolution of Christian doctrine, it was given important church and national value. In Byzantium, it became a testament to the religious tradition and helped form a powerful national identity. The images of the saints symbolized and confirmed the unity of faith. "The demonstrative worship of the icons served as a reason for the church to regulate the cult" [Belting, 2002, 42, 13], and formed the conventional rituals of worshiping the saints.

From the beginning the icon was a sign of God's mercy. The need for an icon, as a symbol of patronage, has always sharply emerged in times of crisis. The need to see a patron, to turn to him, went from temples to homes, and thus the cult of the saints continued in personal use [Belting, 2002, 54]. In homes they reminded of a certain ritual, a duty; at the same time they prompted a prayer. Therefore, in the early period of Christianity, bishops encouraged the faithful to pray before the Savior, Saint Mary, and other "gods" [Stepovyk 2003, 32].

Throughout the thousand years of the history of the iconography development, there has been a combination of Eastern Christian (dogmatic) principles of perception of the icon with the Western, according to which the church work was deprived of dogmatic and liturgical foundation. Gradually Christian symbolism was replaced by visual artistic aesthetics [Vyacheslavova 2013]. However, in domestic icon the symbolism of the image remained. The main focus was on the motive, the iconography, not the level of its artistic interpretation. The domestic icon of unprofessional (folk) performance, the simplified and conventional depiction of a religious plot, was supported by its symbolic purpose. Most often the plot was reproduced by specific iconography, and only the ornamental content was the choice of the author [Hombrich 2008].

Domestic icon painting became a way of mass popularization of well-known iconographic plots. In Western Europe this occurred in the Age of Enlightenment, when cult of an icon, as high art gradually became secondary and moved into active folk use [Belting, 2002, 36]. In Ukraine this process was delayed by a century. Domestic icon, as a work of folk art of the nineteenth century, became a symbol of a certain socio-cultural environment.

Since the eighteenth century the development of Ukrainian iconography was actively influenced by church doctrine and, in particular, by folk religious customs. Rituals and beliefs spread in rural areas have led to the widespread adoption of domestic icons. The works reflected local artistic traditions, as they were mostly executed by local artisans. They demonstrated the everyday culture of the inhabitants and indicated their religious priorities.

Icons intended for home use have mutated from single originals to multiple copies. The article shows the dynamics of the phenomenon: from the appearance of religious images to their mass production. The purpose of the research is to familiarize the reader with the evolution of Ukrainian domestic iconography and the main types of icons.

Appearance of sacred subjects in Rus' reaches the period of the formation of Christianity (X century). By accepting baptism from the Byzantine Empire, Rus'-Ukraine acquired a perfectly formed religious ritualism and iconography.

The first works of sacred content owned by the inhabitants of Kyivan Rus' (X–XIII centuries) were objects of personal piety [Triska 2018, 1280]. These are body crosses, icons, medallions and other items of individual use (Fig. 1). They were considered amulets – many of them have preserved inscriptions asking for protection and help. Obviously, people wore the image of the saint as a symbol of protection against enemies and disasters. Since the XIX century a large number of items of personal piety in Ukraine has been discovered through archeological researches. The geography of the findings confirms their widespread distribution throughout the territory of Kyivan and Halych Rus'. These were one of the first replicated religious symbols.

|

Fig. 1. The Virgin of Lyubech, stone chest icon, XIII c. Published: Pucko V. Treasury of Ukrainian culture, 2006.

This period is marked by the formation of ancient Rus’ Christian traditions. First of all, the princes introduced the custom of worshiping the saint names of which they were baptized. In particular, Yaroslav the Wise (? –1054) began the homage of St. George (Yurii), his son Izyaslav (1024–1078, baptized Dmytro) – St. Dmytro, Rostyslav Mstyslavych (1108–1167, baptized Michael) – the archangel Michael [Hypatian Codex 1989, 289]. Churches were built in honor of the saints, they were depicted on body icons, medallions, pendants. Princes were identified by these images, reproducing them on princely signets. Instead, icons were displayed on the signets of church hierarchs. Our Lady of the Sign is presented on one of them with the inscription: "Mother of God, protect me, Cosma, Bishop of Galicia" (1157–1165) [Figol 1997, 205].

Saints became the guardians of important professions – the Аrchangel Michael was considered the patron of princes and warriors. The first Ruthenian princes – the saints Boris and Glib, who were canonized in 1072, were prayers "for the land of Rus'". They were respected as patrons of princes and warrior aides and depicted on encolpions (chest crosses) and chest icons [Tersky 2016, 60–62].

We can assume that in ancient times there were already small domestic and travel icons. Hypothetically, this confirms the artifact of the XI century from Novhorod. The double sided workpiece is in the shape of a pentagonal plate (100x80 mm) painted into four parts with inscriptions: on the front – Jesus Christ, Virgin Mary, St. Onuphrius, Theodore of Amasea, on the reverse – St. Michael, St. John, Pope Clement I and Macarius of Egypt. Researchers believe that these could be the holy guardians of the family [Artsikhovsky 1973, 200]. However, whether the icons were a permanent element of Ruthenian (Ukrainian) housing is still unknown.

Complex historical circumstances, such as the invasion of the Mongol Empire into the territory of the Ruthenian principalities in the XIII–XIV centuries, polish expansions, devastating raids of the Crimean Khanate army stalled the preservation of the artifacts of the XIII-XVI centuries.

A new stage in the development of icon painting began during the Cossack Hetmanate (1648–1765). The Cossacks defended and strengthened the position of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Hetmans and Cossack elders were the founders of numerous temples. Iconographers were working on the creation of majestic multilayered iconostases. Their skillfulness is reflected in the particular stylistics of the Baroque icons. Apart from that, secular painting was developed, including portrait painting. Close contact was established between the painter and the customer.

In addition to portraits, icons began to appear in the homes of wealthy residents. The first written mentions about them refer to the XVII century. Archival records show that in the first part of XVII century in Lviv, the interiors of the city residents decorated the pictures of art. Among them, the furrier Nicholas Barch had a canvas icon "Christmas", the patrician Martin Anchovsky – 11 icons of various techniques (1679) [Alexandrovych 1994, 71]. On the territory of Hetman Ukraine, Cossack elders decorated their rooms with icons: Colonels Ivan and Danylo Perehrest from Okhtyrka had fourteen icons with frames, six without frames, one painted on a cypress board, five on white iron, carved gilded iconostasis etc. (from archival descriptions of 1704) [Saverkina 1986, 402]. Ethnographer M. Sumtsov wrote that a large icon of the XVII century "Mater Dolorosa" hung in his family home in the settlement ("sloboda") of Boroml’ in the Kharkiv province [Sumtsov 1905]. We have noticed that in the homes of wealthy residents valuable works dominated, some of which had frames made of precious metals.

Icons of this level were created by masters who worked at monasteries, lords' estates, in town painting workshops, executing orders for church founders and others. To date, only single samples of this type have been preserved. They are technologically and stylistically close to church icons, but usually smaller in size. Most often they were painted on boards glued and fastened with splines on the back. A characteristic technological feature of a professional domestic icon is the "ark" – a smooth recess throughout the plane made by the method of wood carving. These art works were painted on the prepared surface with the application of a special smooth background – "levkas". Exquisite ornaments (cut with light relief) were performed on it, and gilded afterwards. The collection of the Kyiv-Pechersk Reserve contains many similar artifacts of the second part of XVIII century. These are "Deusus", "Okhtyrka Mother of God", different types of "The Virgin and Child" (presented at the "Revived Treasures of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra” exhibition from the collection of the National Kyiv-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Reserve, Kyiv, 2018). They may have been made by the painters of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra.

A striking example of domestic icon created by a professional master is "St. Tetiana" (Fig. 2). The icon is distinguished by relief modeled and ornamented background decor, gilding, rich floral painting of clothing and other elements. The choice of iconography indicates that it was a nominal icon (Tetiana did not belong to the common and popular saints).

|

Fig. 2. St. Tatiana. Domestic icon, wood, oil, gilding, second part of XVIIIth c., pr. collection.

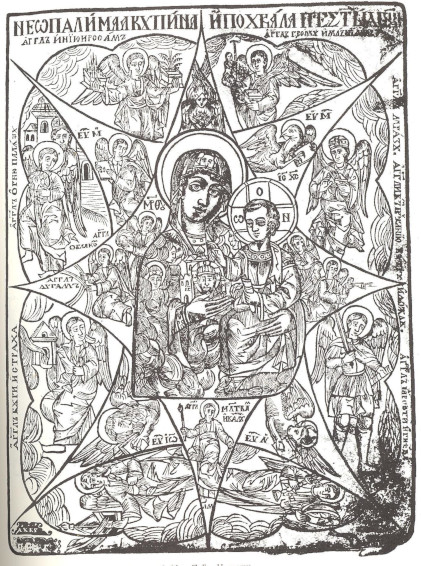

Alternative to valued icons were paper icons. Printing of such icons has gained mass development with the spread of book printing. Describing the voyage to Ukraine (1655), Paul of Aleppo wrote down that the pilgrims of Kyiv purchased paper icons from the printing house of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra [Aleppo 1897]. It is known that one of the first large-format prints were "Kyiv printed sheets" (1626–1628). Eight of them have survived to this day – among the examples are the "Virgin Mary of the Burning Bush" (Fig. 3), which was later reproduced on domestic icons.

|

Fig. 3. Engravers L.M; P.B. Virgin Mary of the Burning Bush. Woodcut of the Kyiv-Pechersk Monastery, 1626. Published: Ukrainian graphic of the XI–beginning of XX c., author-compilerVyunyk A. K, 1994.

Sometimes high-quality graphic prints of the XVII–XVIII centuries replaced icons in churches and szlachta (a legally privileged noble class in the Kingdom of Poland) chambers [Fomenko 2002, 358]. The archives contain information that in the house of the Cossack colonel Sulima in 1766, among the five icons were three on paper [Sulimovsky 1884, 107]. The collection of the monk of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra Dosyfey (1775–1855) also contained six icons on paper "except 12 rare icons on the wood of famous artists" [Zayec 2015, 210].

Over time, more engravers performed graphic versions of the famous temple icons (Fig. 4). In addition, such prints were made by craftsman and folk masters. The woodcuts of folk masters are preserved in the museums of Lviv. The images of popular saints ("St. George", "Archangel Michael", "St. Nicholas", "St. Barbara" etc.) that were small in size, 15x20 cm, were provided with a "picture" completion. They were presented in a decorative frame and were sometimes painted.

|

Fig. 4. The Virgin of Pochaiv. Engraving, 18th c. Published: Ukrainian Graphics of XI-beginning of XX c., author-compiler Vyunyk A.K., 1994.

Signs of the evolution of domestic iconography are lithographs glued to a board. They were conveniently placed on shelves for icons. Graphic religious stories on boards from the Kyiv and Moscow printing houses were seen at fairs by the Swedish diplomat Johann Philip Kilburger (1674) [Kilburger]. The National Museum in Lviv contains several analogues of the XVII-XVIII centuries – "St. Nicholas" and "St. Paraskeva" [Shpak 2006, 200, 204]. The woodcuts were glued to a larger surface, which was painted with an ornament. Thus, the "collage" became the holistic appearance of the icon.

Paper prints promoted various iconographic types of icons and they were convenient samples for reproduction. Later appeared folk masters, often self-taught, who copied them, transforming into hand-drawn icons.

One of the folk domestic icons, dated to the second part of XVIII century, was published in 1913 (Fig. 5). This is an image of St. Paraskeva with a cross and a scroll in her hands. Her nimbus is decorated with a loral garland, and the figure is presented in a simplified and generalized way. This artifact hypothetically indicates the appearance of the hand-drawn icon of folk performance. Subsequently, this type of image of the saints will become one of the most popular in the nineteenth century.

|

Fig. 5. St. Paraskeva. Domestic icon, wood, oil, second part of XVIIIth c. Published: Art in Southern Russia. Painting, graphics, art print. Kyiv, 1913, № 11–12.

Domestic icons (popularly named as "images", "gods") have become most widespread in the second part of XIX century. During this period, they became an integral part of rural housing and occupied a prominent place in the room above the table. This place was called Pokut' because the table was usually placed in a corner (hence the name). Above the table there was a row, or several rows of icons, which together with the svolok (the main wooden beam under the ceiling) (Fig. 6), sometimes with the testimonial inscription to Jesus Christ, formed a sacred corner. Often, the icons were placed on a specially made shelf – obraznyk, bozhnyk.

|

Fig. 6. Interior of the Hutsul house in the exposition of the National Museum of Hutsul and Pokuttya, Kolomyya, Ukraine (photo by A. Kis’, 2008).

Icons, "images", "gods" were the main and often the only decoration of the Ukrainian house – so every house owner tried to collect them as much as possible, buying them at fairs from local painters. They were decorated with white towels, weaving or embroidery, and flowers; beside them were stored consecrated herbs, liturgical books, etc. In front of the icons hung a small lamp, which was lit on significant holidays. Below it was attached a colorful painted ornament "Easter egg" (pysanka – a hollowed out chicken egg, painted on Easter). If there were no lamps, then a home-made wax candle was lit and attached to the bozhnyk [Chubynsky 1872, 383].

Most of the preserved domestic icons are wood-based. They have different sizes – drawn on small, medium and large boards, the exact parameters of which do not match (about 20x30 cm, 30x40 cm, 40x60 cm). People used alder, linden, pine, rarely spruce for the icons [Popova 1989, 44]. The base on the back (like the church icons) was fastened with splines (one, two, depending on the format). Smaller icons were performed on a solid board with no splines. The surface was primed with an adhesive solution. Non-standard dimensions indicate that the painters were dependent on the available material and painted on it by hand, without sketches (specially prepared drawing). Only in the settlement of Borysivka, where the production of icons was numerous and serial, the painters used to draw contours with the powder (a special linear pattern with perforation) [Shulika 2019, 61].

The specificity of Ukrainian icons for homes is their different artistic level (the issue of authorship and specific centers is the topic of a separate study). More unified works came from art icon shops in cities and towns (such as Kyiv, Chernihiv, Lviv, etc.). However, there is evidence of rural painters, cantors, who painted custom icons, traveling from village to village, selling finished works at fairs, etc. [Lykhach 2000, 21].

Some of the icons are made to a certain "standard" and are of the same type. Other works tend to appeal to folk primitives, each of which is unique and authorial. For example, compared by stylistics and method of execution, the researcher of the Ukrainian domestic icon O. Nayden divides the Polissyan folk works into handicrafts (made in icon-painting workshops), naive authorial (created by single masters, in particular, by cantors of the village and town churches); icons with elements of experience, drawn by people with certain skills, but with folk-naive worldview; copied icons, or "reflections" of famous works of religious subjects [Naiden 2013, 1].

|

Fig. 7. Christ the Savior. Domestic icon, Chernihiv region. Wood, oil, XIX c. Published: Folk icon of Chernihiv region, 2015.

One of the centers where "same type" icons were created was Chernihiv region. The distinctiveness of the style indicates the existence of a significant centre with its own artistic traditions [Romaniv-Triska 2015, 40]. About thirty icons of various iconography were performed here. Each center was characterized by a special selection of subjects. The main icons were "Christ the Savior" and "The Virgin and Child". They were called "God's blessing" – parents used them to bless young couples for marriage (Fig. 7, 8). In addition, local iconographic types were popular. Many domestic Mother of God icons come from area names: The Virgin of Pochaiv, Tykhvin, Kazan, Kursk, Okhtyr, Three-handed Virgin and others. Particular importance was given to the "Virgin Mary of the Burning Bush" – it was believed that this icon was able to save houses from fire.

|

Fig. 8. The Virgin of Pochaiv. Domestic icon, Chernihiv Region. Wood, oil, XIX c. Published: Folk icon of Chernihiv region, 2015.

Most common were single-person icons. They depicted saints, who began to be worshiped in the times of Kyivan Rus' – Nicholas (Fig. 9), George (Yurii), Barbara, Paraskeva, Panteleimon, Prophet Elijah, Archangel Michael, Apostles Peter and Paul. Some of the favorite icons where those with St. Julian, the guardian of children, Saviors from Diseases and Epidemics – St. Vlas and St. Harlampius, guardians of animals, in particular horses – St. Florian and Lavr, etc.

|

Fig. 9. St. Nicholas. Domestic icon, Dnieper Region. Wood, oil, XIX c. Lviv, pr. collection.

A characteristic feature of icon workshops was a similar style of painting. Chernihiv icons have a special background. It imitated engraving and gilding of church icons, and was painted with small ocher-yellow ornaments. The icons were dominated by realistic trends. Despite the fact that dozens of samples with the same name have been preserved, they are distinguished by portrait features of saints, ornaments, and nuances of painting.

Particularly powerful and unified center of domestic iconography was the settlement of Borysivka (Slobidska Ukraine, today on the territory of Russia). The icons of Borysivka are recognized by the realistically drawn faces of the saints. Figures in bright clothes are usually presented on a blue background. Favorite effect of painters was light-shadow modeling. They performed it very skillfully, applying it to the heavenly radiance, nimbuses in the form of rays etc. The lack of floral decor was compensated by the masters with a special frame - it was squeezed out of foil and fastened to the icon. At the same time, the frame was decorated with flowers made of colored paper. The whole structure was inserted into a glass icon case that protected the image from damage (Fig. 10). Borysivka was the most productive and mass center of the Ukrainian domestic icon [Shulika 2019, 34].

|

Fig. 10. Deusus. Domestic icon, kiot. Slobozhanshchyna. Wood, oil, foil, artificial flowers, the end of XIXth – beginning XXth c. Published: Ukrainian icon. The village of Borysivka, late XIXth – early XXth century.

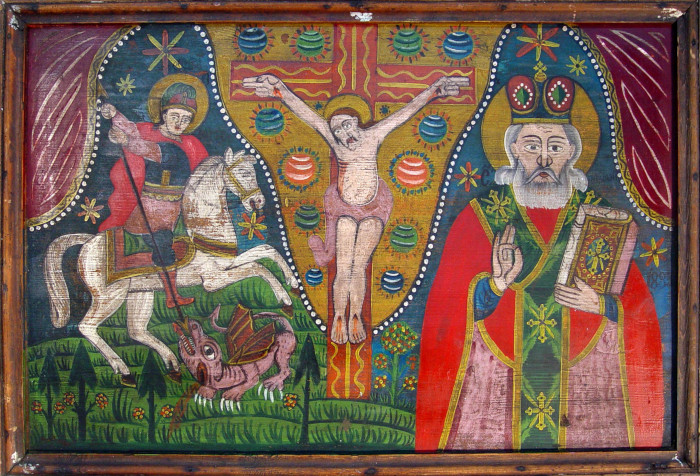

The opposite of Borysivka were the icons on wood from Pokuttya and Bukovyna. These are samples of the folk primitive – broad, bulky, with thick contours, without light-shade nuances. They were painted individually (not in series) in accordance with local artistic traditions and certain iconography (Fig. 11).

|

Fig. 11. St. George the Dragon Slayer, Crucifixion, St. Nicholas. Domestic icon, Bukovyna. Wood, oil, 1883, pr. collection.

The development of domestic iconography was accompanied by the development of new techniques. Because this happened in different environments, many varieties and styles of iconic interpretations have been preserved.

The works on canvas are distinguished by their particular stylistic richness. They are large, mostly long (up to 2m) multi-plot icons (Fig. 12). Their exact purpose is unknown – it is possible that the icons were ordered by wealthy people who tried to furnish their home to resemble a church [Naiden 2009, 494]. They were performed on home-made fabric.

|

Fig. 12. St. John the Warrior, Christ the Savior, St. Paraskeva, St. Barbara. Domestic icon, Podillya. Canvas, oil, second part of the XIX c., pr. collection.

The main painting center was located in Podillya, but the icons from Lviv, Cherkasy, and other regions were also preserved. Most Podillian icons feature two or more subjects. These are generational images of saints, separated by a linear frame and sometimes by the color of the background. One of the characteristic examples depicts "Christ the Savior and St. Paraskeva", with “St. John the Warrior" and "St. Barbara" on the sides (Fig. 12). The composition center is a large flower bouquet that separates and combines two themes. Generally, the characteristic feature of Podillya's icons on the canvas is large, exquisite floral arrangements. They supplemented all the subjects. They give the icons special colorfulness, contrast of colors and shapes, bringing the images closer to the folk carpets.

Icons on glass were distributed only in the territory of Western Ukraine (Huculszczyna, Pokuttya, partly Bukovyna and Nadsiannya). This technique was borrowed from neighboring countries – Romanian, Slovak, Silesian icons that were sold at local fairs. The icons on the glass were not made for a long time, specifically from the middle of XIX century to the 30's of the XX century [Romaniv-Triska 2008, 13]. Early works were performed on glass, and later on they used a factory basis. Glass was the perfect material for plot replication. It was applied to the lithograph or outline and copied. This drawing technique had many advantages – the image, painted on the back of the glass was protected by the shiny surface of the glass. At the same time, the lining of the gilding enhanced the colorful effect and added decorativeness to the icons.

Works on glass differ in subjects. One of the main ones was the "Crucifixion" or "Crucifixion with Bystanders", which was often accompanied by other saints. The leitmotif was the three-part composition: "The Virgin and Child, Crucifixion, St. Nicholas". One-person samples were more traditional – they represented saints Nicholas, George, Barbara, Catherine, Paraskeva, John Nepomuk, Archangel Michael. The Hutsul-Pokut icons on the glass are unique in style. Many of them are dominated by bright red backgrounds, which is why they are commonly referred to as "red images" (Fig. 13). They are "non-canonical" – arbitrarily painted. The painters developed their own colorful scheme, using 5 – 6 colors alternately. The masters marked the border of the garments only in yellow, the faces of the saints in white. Their clothes were red on green background, green on red background, etc. Icons on glass gravitate to exquisitely decorative and bright in color folk primitives.

|

Fig. 13. Crucifixion with Bystanders, The Virgin and Child. Domestic icon, Pokuttya. Glass, oil, end of the XIXth c. Published: Folk icon on glass, 2008.

Domestic icons were a semantic and aesthetic, artistic expression of rural Christian culture in Ukraine. Ethnographer O. Tarasov rightly emphasizes that in these works the «system of "automatisms" of the collective consciousness is preserved and conditioned by culture, language, religion and social life» [Tarasov 1995, VIII].

Traditions of domestic iconography were shaped from single artifacts to replicates. Their specificity was a compilation of techniques and capabilities. This was facilitated by a wide range of performers – masters from different artistic backgrounds, artisans and amateur painters. The uniqueness of the Ukrainian domestic icon is the reproduction of traditional Christian religiosity by folk art.

Aleppo P.1897, Patriarch Macarius of Antioch travels to Russia in the mid-seventeenth century, described by his son Archdeacon Paul Aleppo, Moscow, Ed. 2.

Alexandrovich V. 1994, Fine arts methods in the activity of masters of Western Ukrainian painting of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries//Notes of the T. Shevchenko Scientific Society", T. 227: 57–87.

Artikhovsky A.V. 1973, Icon preparation from Novgorod //Byzantium, the Southern Slavs and Ancient Russia, Western Europe: Art and Culture, Moscow: Science, 199–202.

Belting H. 2002, Image and Cult. History of the image before the era of art. Moscow: Progress-Tradition.

Chubinskiy P. 1872, Proceedings of the ethnographic-statistical expedition to the Southwest Land, Spb., Vol. 7.

Figol M. 1997, Art of Ancient Halych, Kyiv: Art.

Fomenko V. 2002, Prints of the type of "folk pictures" in the system of Ukrainian art culture //IV Gonchar’s Readings: Traditional and personal in art, Kyiv: UC Gonchar Museum, 354–366.

Gombrich E. 2008, On problems and boundaries of iconology // Migunov A. S. Aesthetics and theory of art of XX century. Moscow: Progress-Tradition, 656–680.

Hierodiacon Janouary (Gonchar), Shulika V. 2019, Ukrainian icon. The village of Borysivka, late XIXth – early XXth century, Kyiv: Ivan Gonchar Museum.

Hypatian Codex 1989, Kyiv: Dnipro.

Kielburger I.F. 1679, Short information about Russian trade, how it was made through Russia in 1674 // www.history/syktnet/en/01/06/012.html

Likhach L., Kornienko M., 2000, Icons of the Shevchenko Land, Kyiv: Rodovid

Naiden O. 2009, Folk icon of the Dnieper Region in the context of peasant cultural space, Kyiv: Institute of Art Studies, Folklore and Ethnology by M.T. Rilsky NASU

Naiden O. 2013, Folk painting // http://bervy.org.ua/2013/05/narodnyj-zhyvopys-2/

Popova L.M. 1989, Some Aspects of Ukrainian folk iconography of the nineteenth century // Folk Art and Ethnography, № 2: 43–47.

Romaniv-Triska O. Ed., 2008, Folk Icon on Glass, Lviv: The Institute of Art Collecting, Shevchenko Scientific Society.

Romaniv-Triska O., Kis A., Molody O., Ed., 2015, Folk icon of the Chernihiv Region, Lviv: The Institute of Art Collecting, Shevchenko Scientific Society.

Saverkina I.V. 1987, Unknown sources about the life of Peter time // Cultural memo. New discoveries, Leningrad: Science, 385–40.

Shpak O. 2006, Ukrainian folk engraving of the XVII - XIX centuries, Lviv: The Institute of Ethnology of NAS of Ukraine.

Stepovyk D. 2003. Iconology and Iconography. Kyiv: Ivano-Frankivsk.

Sulimov archive 1884, Kyiv.

Sumtsov N.O. 1905, The Ukrainian Antiquity. The history of Ukrainian icon painting, Kharkov // http://elib.nplu.org/view.html?id=369

Tarasov O. Yu. 1995, Icon and piety. Essays on iconic affairs in imperial Russia, Moscow: Progress-Culture.

Tersky S.V. 2016, The cult of holy warriors and military honors in the Galicia-Volyn army // http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/vnv_2016_25_7

Triska O. 2018, The origins of the Ukrainian domestic icon: the patronal principle of holiness//The Ethnology Notebooks, № 5 (143): 1279–1289.

Vyacheslavova O. 2013, The Problem of Fine Path in Christian Philosophical-Aesthetic Discourse (Part 1) // http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/apitphk_2013_31_39

Zayets O.V. 2015, Collection of Hieromonk Dosifey (Ivashchenko) of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra as a source of knowledge // Church, Science, Society: Issues of interaction. XIII International scientific conference, Kyiv (May 27–29, 2015): 209–212.