Table of Contents

Abstract. In the history of forming of visual anthropology as a method of intercultural communication in Russia up to the present time documentary cinematograph takes a dominant lead. Taking into account the change of ideology and the information technologies’ development level there can be marked several stages:

Already in the pre-revolutionary period the documentary cinematograph started realizing its cognitive function, which made its core function with time. Unpretentious short fragments of the chronicle are nowadays considered the rare evidences of the passed life.

After the revolution the new state from its very steps set a task for cinematography to form a “new man”. This movement was headed by Dziga Vertov, an ideologist of a special vision of reality via cinema camera and via influencing the spectators through the documentary screen. His “kino-pravda” had become a symbol for the researchers of the real world with the help of the movie language. The movie “A Sixth Part of the World” became an unprecedented project of a simultaneous documenting of lives of different peoples in vast territories of the country, and it inspired other documentary filmmakers for making movies on ethnographic topics.

The post-war period was the time of a reviewing “kino-atlas” based on popular science movies – “travelogues”, where just a little time was spared to ethnographic topic. The common cinema target became showing the achievements of the Soviet system. Participation of scientific community was limited to advisor’s role. Just in some particular cases there were created university and academic ethnographic movies.

The first in the USSR territory festival of visual anthropology in Parnu town offered a new approach to showing the life of human communities. The main challenge of the film directors was to reveal the essential features of lives of those people who confided to tell their stories. Such principles of visual anthropology as authenticity and moral responsibility towards the depicted culture became a challenge to the attitudes to forming the mindset of the spectator in an available form.

The contemporary period of visual anthropology development is marked with search of ways of integration of scientific approaches of modern anthropology and a newly forming ethical and aesthetical language of the documentary cinema.

Keywords. visual anthropology, intercultural communication in Russia, documentary cinematograph, Dziga Vertov, popular science movies – “travelogues”, integration of scientific approaches of modern anthropology

There is a huge variety of opinions when one considers the purposes and limits of visual anthropology [Aleksandrov et. al. 2007; Pink 2006]. In the present article I shall proceed from the definition of the basic and specific function of visual anthropology, which distinguishes it from similar activities, i.e. carrying out intercultural communication via audio-visual means basing on anthropological researches [Aleksandrov 2017, 16].

The starting point for forming a new discipline was the conviction of its creators in definite advantages of cinematograph in comparison to other information systems. The ability to depict time spans of a certain event provided a higher extent of authenticity, while the balanced synthesis of audio-visual languages of contemporary movies facilitated high level of emotional and aesthetical expression.

The encounter of Russian academic society and visual anthropology happened later than in other European countries, no sooner than the 2nd half of the 90’s of the last century, coinciding with important democratic changes in the social life.

And though filmmaking of ethnographic subject in Russia had been carried out practically since the moment of invention of cinema, ethnographic science and documentary cinematography had existed in parallel worlds for a long time, coinciding just occasionally. Such situation not just not promise in perspective, but it did not favour (when it finally happened) to fast and smooth synthesis of the two types of activities, which to a great extent defined the state of the present time Russian visual anthropology. Taking into consideration change of ideological principles and level of information technologies’ development, in the process of its formation several stages could be outlined:

News-reel shooting of ethnographic subject in the Russian Empire (1896-1916)

From “Kino-Pravda” to forming a “new man” (1918-1941)

The USSR Travelogues (1946-1987)

After the first festival of visual anthropology (from 1987 till the present time)

Only a year after the first cinema performance in Paris, that denominated the start of the cinematography era, the operators of the Lumiére Brothers company started shooting in the territory of Russia, filming in May 1896 the crowning of the Emperor Nicolas II. It was a significant work for that time (it lasted almost 2 minutes), well-preserved up to the present time and quite well-known. Among the other pompous frames of the official ceremony there was an ethnographical episode there – a procession of representatives of different peoples, populating the outskirts of the empire, in their native costumes.

|

Pic. 1. Shot from a film Coronation of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna

That was a kind of a starting point in the Russian history of cinematography. Gradually in Moscow and Saint-Petersburg, and then in the other cities of the empire there started emerging cinemas, where during the lead-in caption there was demonstrated the coronation movie. There are no direct evidences that Boleslaw Matuszewski was among the Lumiére shooting crew, but, according to a book he published in Paris in 1898, he was also shooting Nicolas II upon his permission[1].

|

Pic. 2. Bolesław Matuszewski

B. Matuszewski not just managed to shoot 16 movies with participation of the Imperial Romanov family on his own in 1897-1898, but already in one of his letters to the Minister of the Imperial Court, in February of 1900, he drafted a proposal of creating a cinema library [Batalin, Malysheva 2011, 8]. In his book with an expressive title A New Source of History: The Creation of a Depository for Historical Cinematography (Une nouvelle source de l’Histoire. Creation dé cinematographie historique) he, not without vanity, and quite reasonably, names himself the “precursor” of creating of film libraries and film vaults. His ideas of cinematography as a historical source and a new means of scientific research have retained their relevance till today.

Vladimir Magidov, a Russian researcher of B. Matuszewski’s creative career, notes that the cinematographic interests of the author of the first books about the cinema were not limited with the films about the Imperial family. In the beginning of the 20th century he took on the role of the “forerunner” in the field of visual anthropology, conducting ethnographic filming in provinces of Poland that was part of the Russian Empire those years.

After the visit of the Lumiére operators and Matuszewski’s activity cinematography became general rage and an permanent entertainment of the Imperial Household. A co-proprietor of K.E. von Hahn & Co company that had the exclusive rights, photographer and operator Alexander Yagelsky, till the rest of his life in 1916 was shooting films and arranging regular demonstrations of life events of the Imperial Family. And even though the movies were cut for internal use, their separate fragments of official character were demonstrated in public cinemas [Batalin, Malysheva 2011, 8-9][2].

|

Pic. 3. Alexander Yagelsky

Compared to the films by A.Yagelsky, the materials shot by B.Matuszewsky seem to have not been preserved as well as the film shoots by cameramen of the Lumiére Brothers, who in the end of the 19th and the first years of the 20th century had been actively exploring the boundlessness of Russia. They made it to the Caucasus and to the Urals, they were shooting films and organized shows in various cities. In particular, there is a fact that a photographer Alfred Fedetsky, one of the first Russian filmmakers, could not meet the competition with them in Kharkiv. Among the movies that he demonstrated to the audience was a record of Orenburg Cossacks Regiment [Mislavskij 2006, 165]. From that time and on the “Cossack” theme had become one of the most popular among the documentary filmmakers.

Before 1908 on the Russian screens there prevailed mostly French film companies Gaumont and Pathé which replaced the Lumiére Brothers. Their main production was represented by staged entertainment movies. Among the newsreel there dominated official ceremonies, but the interest was gradually shifting toward the “life scenes”. The greatest sensation became a famous documentary film by Pathé Cossacks of the Don, which was booked out in record-breaking time. Following the Cossacks of the Don, Pathé launches a series of scenic documentary of 21 series entitled Picturesque Russia, that included the tapes of ethnographical character: Scenes from Caucasian life, Travels through Russia, A Fish Factory in Astrakhan [Lebedev 1947, 14-15]. It is doubtful that the growing diversity of the synopsis was caused by conscious strive of screen reporters for conduct of communication between representatives of different cultures. Their target was to struggle with commercial competitors and ambition of surprising the public with wondrous stories. And yet, in the quest for originality and sensations they were inevitably widening spectators’ horizons, demonstrating them, even if limitedly, the life of close and faraway worlds. Becoming more available, a means of information starts to meet proactively its challenge of indirect intercultural communication.

One of the first Russian film studios was set up by Aleksandr Drankov. In the beginning of 1908 his company produced and put on the market 17 scenic and chronicle movies of various topics, including Yew Sunday in Moscow, Khitrov Marketplace, Views of Warsaw, Finland [Lebedev 1947, 14-15]. However, the movie that made Drankov famous was the coverage of Leo Tolstoi who had long been keeping the cameramen away. Persistency and craft helped the ingenious filmmaker win the confidence of the great writer. Having learnt Tolstoi’s interests, Drankov, among other things, shot an ethnographical film A Peasant Wedding. In total, he cut about five movies where he depicted the last years of Leo Tolstoi surrounded by his family. Drankov’s success aroused a great interest of his rivals. Thus the last years of Leo Tolstoi’s life were largely filmed by other companies, and among them Aleksandr Khanzhonkov who came into the spotlight those years. The total number of documentary films about Tolstoi played in the period from 1908 till 1913 on the Russian screen was twenty-two [Glebova 2016].

|

Pic. 4. A shot from the filming of A. Drankov Family of Leo Tolstoy

The biggest libraries of chronicle movies that survived to our days and that keep documented the life of particular communities within a long period of time are the documentaries of the two families: the Imperial Family and Leo Tolstoi’s. Already in the first years of the Soviet Republic they enjoyed the attention of the filmmakers. Later in the article it will be told how those movies were used.

Starting 1907 large film studios, as well as individuals, set for progressive discovering the vast territory of the country. A famous photographer Veniamin Metenkov was actively working in the Urals and the Volga regions. Apart from a great number of fine photographs, some of which were used in the movie named “Fragile Moments” of History directed by Vladimir Chinenov in 1994, he also made a film named Views of the Urals [Baklin, Kalashnikov 2003, 184].

Gaining ground a company named “A. Khanzhonkov & Co.” from its very establishment, among fiction movies, paid much attention to shooting scenic and ethnographical films. An experienced cinematographer Vladimir Siversen shoots a movie named Trip to the Rivers Zelenchuk in Caucasus in 1908.

A student of the Saint-Petersburg University Nikolay Minervin, who had been making films about the Caucasus peoples, joins Khanzhonkov’s company. Those miraculously spared films have been recently used by a film Director Valeriy Timoshchenko in his movie named The Lost World [Gibert, Nyrkova 2016, 71].

Khanzhonkov’s company had also a scientific department headed by its manager, Senior Cameraman Fedor Bremer. He can be considered the first cinematographer who was shooting in hard-to-reach and unpopular regions of the north of Russia. In 1913 Bremer was sent on an expedition beyond the Arctic Circle. On his long way across the south seas he was shooting films in India, in Ceylon. The “Kolyma” steamer, on board of which the operator was crossing the Arctic Ocean, was ice-nipped and had to face a forced overwintering.

For the three years of the voyage Bremer made no fewer than 20 movies that had depicted the peoples of Kamchatka, the Baikal region, Kalmykia and Chukotka. He also cut a movie The Views of the Primorye Territory cut on the expedition of Vladimir Arsenyev, a famous researcher of the peoples of the Far East. That was probably the first case in Russia of collaboration of documentary filmmaker with scientist ethnographer. Fragments from F. Bremer’s movies were later (in 1927) included by a Soviet cinematographer Vladimir Erofeev into his film named Beyond the Arctic Circle [Deryabin 1995, 71; Deryabin 1999, 16; Vishnevsky 1996, 204-226]. Neither pictures of Fedor Bremer, nor the exact date of his death are known.

|

Pic. 5. A shot from the film Beyond the Arctic Circle

Unlikely as it may seem, there were things more important than shooting ethnographic films during the war and revolution years. But it was exactly in 1917, a threshold year for the country, when a Finnish archaeologist and anthropologist Sakari Pälsi undertook a railroad trip from Helsinki to Vladivostok. Then on a fishing boat the expedition sailed to the north, where during the summer season they were shooting a movie on the Chukotka coast of the Arctic Ocean. In Helsinki the film was assembled, screened and went to oblivion for a long while. No earlier than in 1976 a part of the remaining materials was found and used in a restored movie Arktisia matkakuvia [Chuyko 2017].

It was the first case subsequently repeated only a quarter of a century later, where the ethnographic topic documentary was carried out by the scientist personally.

The World War I and subsequent revolution period transformed the intercultural function of cinematography quite radically, shifting focus from educational to propaganda purposes. The republic faced a serious problem of retaining the power and building a new country on the ruins of the empire, which immediately demanded to win over the attention and sympathy of the masses of people. There was a need of simple and efficient mass media. The inherited nationalized film industry and a small number of top-gun cinematographers could not manage solving of the new challenges. There was a demand for people enthusiastically committed to achieve the dreams of a new world order. A student of Neurological Institute Denis Kaufman, who became famous under the name of Dziga Vertov, was the right man for that work.

He rapidly got familiar with the profession on political campaign trains of the Civil War, participating in newsreel shooting and communicating with the spectators during the film demonstrations. Starting 1918 he releases a Kino-Nedelya series,which preserved till today the reverberations of quickly changing fantastical events of that time [Medvedev 2014, Lemberg1976, 80]. In June of 1922 Vertov releases the Kino-Pravda, series, episode №1. In total there were 24 episodes, some of which can now be found on the Internet. Even few viewings are enough for understanding the origins of Vertov’s life philosophy and determining why the the series name half a century later became a symbol of forward movement of European cinematographers. In the course of the first episode showing the life of homeless children of the Volga region on the railway station Melekess a full-screen title reads «Save the hungry children!», and in the end, after the episode showing the skin and bone children, the title reads «Carry us out!».

|

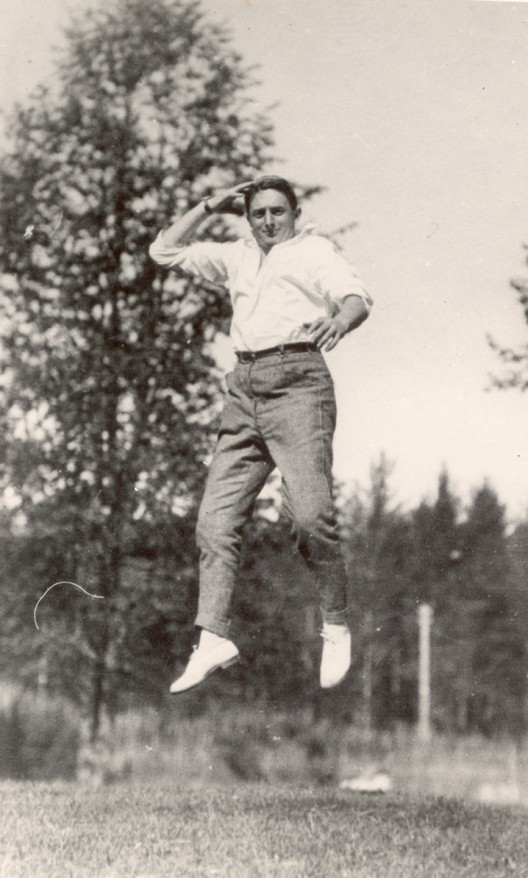

Pic. 6. Dziga Vertov opens the world

|

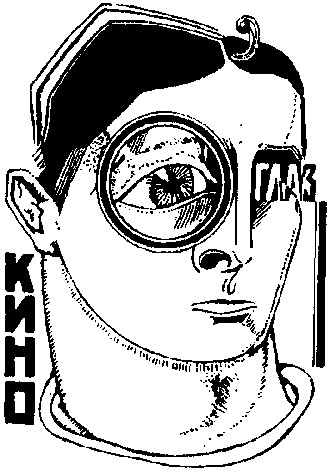

Pic. 7. Vertov - Kino-Eye. Caricature by artist Piotr Galajev

Vertov advances a slogan «Good Newsreel Now!», and he doesn’t object when sceptics remake it for «Away with Art Cinematography!». From then and on he started his steady struggle under the slogan of Kinopravda against all kinds of traditional arts and for the art of documentation.

|

Pic. 8. Mikhail Kaufman - the first of the “kinoks”

It was amazing how masterly Vertov and his brother and companion Mikhail Kaufman managed to work with inconvenient box cameras. Imprefect equipment, however, did not prevent Vertov, the supporter of actuality, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, avant-gardist and follower of proletarian culture, from foreseeing the tendencies of the contemporary cinema language in the manifesto WE of 1922, and expressing his political views in a controversial form:

WE proclaim the old films, based on the romance, theatrical films and the like, to be leprous.

-Keep away from them!

-Keep your eyes off them!

-They’re mortally dangerous!

-Contagious…

In controversial fervour he would even write: «WE temporarily exclude man as a subject for film» [Vertov 1966, 45-46].

However, manifest proclamations were normal for the followers of the proletarian art. Back in 1919 Kazimir Malevich in his program of Left non-objective subjects declared war to academism [Malevich 1933, 110].

Certainly, with time Vertov specified, modified and liberalized the language, correlating it with his creative experience and responding to numerous critics, even though he remained faithful to his core principles for the rest of his life.

It must be remembered that back in 1918 Vertov, to make an experiment on himself, jumped from a two-meters’ heights just to watch in a low-speed mode the reflection of the experienced feelings on his face afterwards. 10 years later he was the first in the history of documentary cinema who simultaneously and in a long take cut continuous stories told by several people, and thus he destroyed his own image of inventor of rapid cuts, with the help of which he used to turn real events into a slogan sign. Thus Vertov brought to action his delayed, but permanent need for using the camera for revealing of the emotional state of a human being...

Vertov was documenting the «life as it is, life-unaware», without actors or montage constructions, without naming himself film director. He was an «instructing coordinator», «engineer», «observer» of the real life caught by the camera [Roshal 1982, 28].

In 1926 Vertov shot a documentary named A Sixth Part of the World, where he attempted to introduce the life of the peoples of a big multinational country. Despite an obvious agitation task, the film presented a wide and colourful plethora of pictures of Russia. Contemporary researchers can consider the documentary a kind of ethnographic review, even though it was put in Vertov’s favourite pompous poster form. Like all other works of this outstanding master, the film is worth a detailed analysis from different points of view, and no less important for the history is the clash story related to the creation of the documentary.

For the collection of materials for the film, the kinoks-operators from Vertov’s group were sent to the most remote parts of the country. In total for carrying out A Sixth Part of the World there were used about 30 thousand meters of film, of which in the movie there were used a little more than a thousand meters. According to the correspondence with the cameramen, Vertov ordered them to grasp as many details as possible, and to pay attention to the peculiarities of daily life of representatives of different peoples characterising their lives in harsh weather conditions. Among other things, one of Vertov’s recommendations to the operators who worked in the North gave an excellent example of instruction for future visual anthropologists: «show your movies to their characters and cut their reactions».

“Kinoks”– operators who were cutting the films for A Sixth Part of the World, sometimes together with other film directors, but usually with the help of film editor Yelizaveta Svilova (the most faithful “kinok”, Dziga Vertov’s wife and permanent editor), later on cut their own movies, normally depicting particular nations: Petr Zotov – movies The Tungus, Dagestan, Bukhara, The Life of National Minorities, Sergei Bendersky and Nikolay Yudin – Hunting and Deer Farming in the Komi Region. Operator Ivan Belyakov in collaboration with Nikolay Lebedev, Vertov’s opponent and critic, recorded in 1928 a film Gates of the Caucasus, and in 1929 a film Nahcho Land telling of life of the Chechens [Deryabin 1995, 65].

Naturally, the possibilities of film equipment and the influence of Vertov’s general style determined relative briefness of episodes and necessity to limit with concise titles instead of abundant comments. Nevertheless, for the contemporary cinematography those films are an expressive testimony of the gone past of the nations that represented different parts of the country. Another Vertov’s associate who later became a famous documentary director, Ilya Kopalin, was excited about collectivization processes among the country folk. In 1930 in the Moscow Region together with cameraman Zotov they recorded a big movie Village, where they used bulky audio equipment for synchronous recording of actual noise.

Thus, Vertov not only made an ethnographical documentary which became one of remarkable production of world documentary filmmaking, but to some extent made an urge for forming the interest for ethnic topic among other Soviet film directors.

There were few people back in those years whom he left unmoved indeed. Esfir Shub did not avoid Vertov’s influence either. His experience in masterful editing of documentary material encouraged the turning of the beginning movie-maker to pre-revolutionary materials forgotten in those years [Shub 1972, 83]. For the ten-year anniversary of the revolution she made a distinctly propagandist movie The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty, and later on in 1928 another movie – Lev Tolstoy and the Russia of Nicholas II. The movies were based on reinterpretation of a chronicle which was to illustrate the title idea.

|

Pic. 9. Esfir Shub

In 1928 an experienced cinematographer Aleksandr Litvinov got engrossed with the ethnographic topic Basing on recommendations of ethnographer Vladimir Arseniev, his film team for half a year had been making a film named Forest People about Udege taiga inhabitants, later on receiving an approval from Robert Flaherty. Subsequently, Litvinov continued working in the Far East and in Siberia, he made over 20 documentaries and fiction films. After the war he was awarded a prize of F.F. Busse for «making films containing valuable documentary materials in ethnography of the Far East nations» [Deryabin 1999, 14-23]. Already in our time a young researcher and film director Ivan Golovnev studied and developed his experience in his documentary The Land of the Udege [Golovnev I. A. 2016, 83-98].

|

Pic. 10. A group photo: on the left Vladimir Arsenyev, on the right - cameraman Mershin and Alexander Litvinov

In 1927 Vladimir Erofeev, who re-energized the northern films of Fedor Bremer, made a movie Roof of the World about the nations of Pamir. Erofeev kept working till the middle of the thirtieth, shooting in Afganistan and Iran till the time when new tasks were placed for cinematographers: documentaries about the nations were replaced with brief subjects in news-reels with obligatory criticism of archaic organization of traditional life and demonstration of the Soviet life achievements [Deryabin 2001, 53-70].

In the Soviet time all the camera recordings are made by professional cinematographers from the state film studios. An exception to the rules was a work by Georgi and Ekaterina Prokofievs – the two scientists of the Kunstcamera, back in those years a head anthropological institute of the Academy of Sciences. Very modest technical equipment and harsh living environment did not disturb the researcher`x`s from documenting the life of the Nenets on the Arctic ocean coast. Recently a specialist of the Kunstcamera Dmitry Arzyutov has restored and included the remained materials into the film Samoyedic Diary [Arzyutov 2016, 187-219].

|

Pic. 11. A group photo: George and Ekaterina Prokofiev, in the center of the bottom row

In the beginning of the 1930th the romantic period of the proletarian art ended. There came other attitudes and expression forms: “To mass character and apprehensibility of the art! To its turning into an ideological weapon of the world October!” [Macza 1933, 635].

The epoch of creative searches ended, passed the time of the Proletkult, the time of the Left Front of the Arts, the time of Mayakovsky and the Soviet avant-garde. To replace the slogan of «forming a new man with new means» that inspired the documentary film makers in the previous period, there was promoted an idea of creation a Kino-atlas of the USSR– a campaign production of popular science films as illustrated study guides aiming to «plant in people’s minds some ideas» [Golovneva E. V., Golovnev I. A. 2016, 149]. Documentary film directors kept working, making no claims to discovering alternative ways of existence and new possibilities of the movie language. Numerous successors of travel films, such as itinerary feature stories, kept being released, but ethnographic topics were far from being focused on.

|

Pic. 12. Vladimir Shneiderov

Vladimir Shneiderov is considered the founder of the travelogue genre in Russia. Back in 1925 he cut a movie named The Great Flight dedicated to an expedition to Mongolia. Being a favourite genre of both the government as the customer and the keen spectators, the itinerary feature story with the help of new technical possibilities had grown into a popular-science film. This travel propaganda genre made dominant in the last years before the World War II and remained so during years after its end. Oksana Sarkisova, a specialist of the Central European University in Budapest, has recently published a detailed cultural study of this type of Soviet documentary film directing [Sarkisova 2017].

After the end of the war, the necessity in propaganda with the help of the documentary films did not fade away. Already in 1960th there worked about 25 newsreel studios. In the average during one year there circulated over a thousand issues of newsreels and about two hundred documentaries of different film length. For example, a Georgian Film Studio alone was annually churning out about 15 documentaries, 20 scientific and teaching films, 42 issues of newsreels named Soviet Georgia [Yutkevich 1966, 399]. In all the cinemas before feature film performances there showed ten-minute newsreels. Some particular documentaries were shown on television that was rapidly becoming a part of people’s life.

Almost all the movies demonstrating various parts of the country were created by a unique pattern: they started with geographical characteristics of the region and its economy, proceeded with achievements in production and agricultural sectors, drew several portraits of heroes of labour, and final episodes spoke of men of art. There were almost no exclusions, because till the end of the seventieth there existed unique guidelines for all the film studios.

Vladimir Shneiderov, the head of the Moscow scientific film studio department, who was responsible for cutting the series Travels in the USSR, referred to Methodology instructions of 1949, which were a kind of guideline for all the other film studios: «to show activities of a human being, a conscious creator of a new landscape and a new life via necessary creation of a set screenplay where generalization and ideological basis plays a very important part» [Shnejderov 1964, 180]. And in another article he said: «They are shooting their movies (…) without distracting the action of the documentary from its educational tasks, without going in for description of psychological collisions of the main characters or turning into a current day event chronicle» [Shnejderov 1970, 404-406]. Following such guidelines, during the time of the department’s existence there were released about 250 newsreels, of 20-minutes’ duration each, and where the ethnographical topic proper occupied just a fourth part, if ever existed.

According to the intentions of the ideologists of the Kino-atlas of the USSR, all this great volume of information was to demonstrate variety and beauty of the most remote places of the huge country and at the same time to show a new Soviet man as a result of the transformation of the backward outskirts of the tsarist Russia into prosperous socialistic republics and regions.

Though in general the travelogue movies may claim to be an exhaustive review of the life of the former Soviet Union peoples, including the small-numbered ones, an anthropologist who refers to those materials has to scrutinize and select the information bit by bit, taking into account the conditions of creating such materials. The possibilities of the cinema equipment of that time poorly coped with the task of realistic reflection of the people’s lifestyle though: it was difficult to conduct any longstanding shooting or make a synchronous sound recording outside the studio.

As the travelogue movies had the status of scientific documentaries, with time they started to involve consulting scientists: geographers and ethnographers in their creation, but their participation in film creation was limited with the requirements set by the studios. In the entire history of existence of the USSR only in some singular cases there were shot movies where interests of researchers could prevail. Among such cases are several ethnographical films created in the motion picture laboratories which existed in the 50th in various major universities. In Lomonosov Moscow State University there were made films The Village of Viriatino and The Kumik Habitat, in Leningrad State University – The Gagauz of Soviet Moldavia, in the Tartu State University – Wedding Ceremony on the Kihnu Island [Kubeev 1958, 47-95]. However, as the works made in university film laboratories rarely reached the Russian State Film and Photo Archive, the chances to find those films are small. At the same time one shouldn’t expect that in these movies the generally accepted canonical rules could be broken or that such films would meet the scientific requirements and adhere to the esthetical perception conditions.

As a rule, film studios were badly equipped and did not specialize in ethnographic subject.

It seems that the only instance when ethnographic documentary was the main occupation, and when for a long time it was conducted by scientists, was in Moscow, in the Miklukho-Maclay Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. A researcher Alexandr Oskin had been shooting movies in expeditions for many years and then making documentaries based on the filmed research materials. His films made in different corners of the country and in Cuba formed the basis of the film archive of the institute.

Later on in the middle of the 90th, his successors in the institute, young anthropologists and editors Nikolay Pluzhnikov, Nikita Khokhlov and Aleksei Vakhrushev created on the basis of the film laboratory the Audiovisual Anthropology Centre of the N.N. Miklukho-Maclay Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In the present time there have been restored and actualized several films cut by A.Oskin. One of the most successful movies is Celebration in Lesgor (1975, 50 min.), depicting an ancient ceremony in the Caucasus Mountains.

|

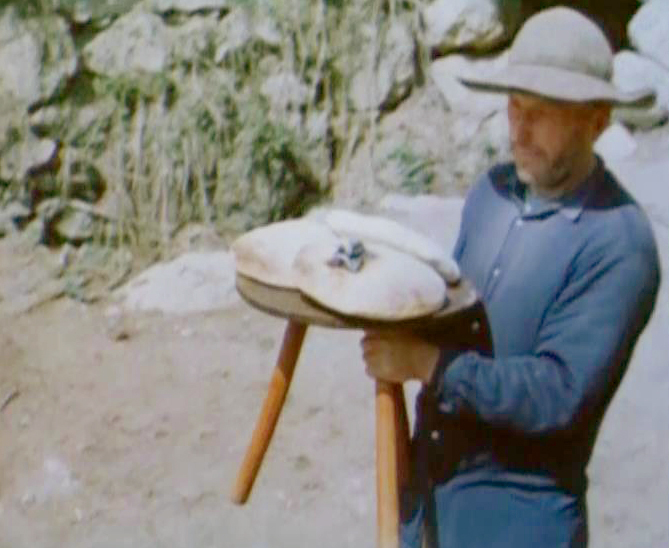

Pic. 13. A shot from the film Celebration in Lesgor

In the middle of the 1960th during film festivals and on club screens of the Soviet Union there start appearing movies of the European New wave, including documentaries. Three years after the performance in Paris of Chronicle of a Summer in Moscow there was released a movie by Viktor Lisakovich Katyusha, and two years later in 1967 there came a movie by Pavel Kogan Look at the Face. In those innovative works the spectators were surprised by sincerity of emotions on excited faces of the people caught by the “hidden camera”.

After a long period Dziga Vertov’s ideas of studying the real life by means of documentary came back from the oblivion and made actual again. The crusted rules of scientific films started to fade away gradually, and the journalistic and science fiction genres began to develop.

Young film directors (some of them will be named further ), and especially in cities relatively remote from the capital, started making ethnographic films more and more often waiving the rules. In Yekaterinburg there worked Anatoly Baluev, Arkady Morozov, Vladimir Yarmoshenko, in Perm – Pavel Pechenkin, in Saratov – Dmitry Lunkov and Alexey Pogrebnoy, in Novosibirsk – Yury Shiller and Valery Solomin. In documentary film studios of the Republics of Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus and the Baltic Republics they make films focused on the life of their peoples.

Though contemporary methods of film shooting are gradually turning into practice of film-makers, in the majority of cases the imperfection of the equipment which did not permit making long synchronized sound shooting was the factor that determined the domination of the popular-science genre.

Using the announcer voiceover, the music, animation and cropping by noddy shots’ technique helps achieving perception efficiency. However, from the other side, active use of these scenic media while facilitating the task of event interpretation by the author, at the same time obscure adequate representation of the real life. Considering the possibilities of the popular-scientific genre from the point of view of intercultural communication, there will always rise a question of what will be more important for the author: authenticity of showing the reality or his strive for an efficient audience impact. In the way of communication such intense for perception and limited in time as a film, finding harmonic balance between the opposite tendencies is a principal and quite a challenging task.

Evolving under the influence of change of ideology and development of information technology, progressing and transforming, this genre kept remaining in high demand for a long time. And even in the Baltics, where the ideological interest weakened first and the questions of national self-determination were particularly sensitive, in the last year of the soviet era scientific-popular films were mainly made with focus on the ethnographic topic

In the end of the 80th, as the result of a team-work of a documentarian Andris Slapiņš and the Moscow researchers Elena Novik and Eduard Alekseyev, who were not just consultants, but rather co-authors of the film director, there was created one of the best films of that period ̶ The Time of Dreams, which depicted the prints of the vanishing culture of Siberian peoples.

|

Pic. 14. Andris Slapiņš

|

Pic. 15. A shot from the film The Time of Dreams

The film directors’ movement which played a prominent role in the struggle for the independence of the Baltic republics was leaded by a writer, publicist and subsequently president of Estonia Lennart Meri. He was the author of a film named The Winds of the Milky Way – one of the best movies cut about the history of Ugro-Finnic peoples.

|

Pic. 16. Lennart Meri

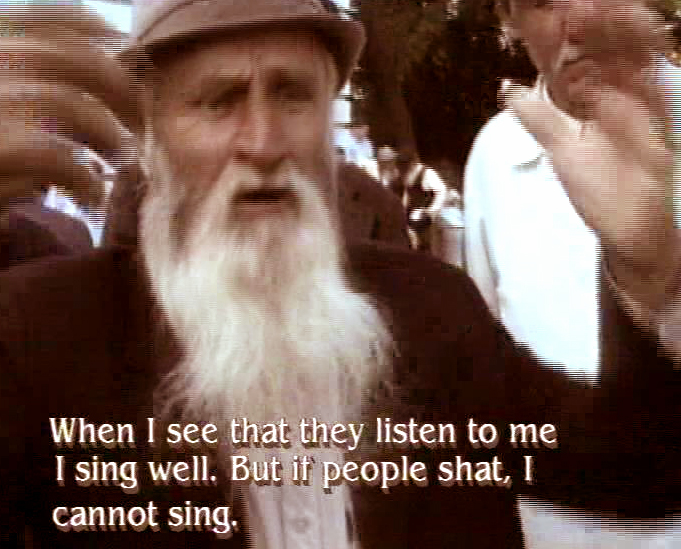

Visual anthropology as a kind of creative activity appeared to the Russian researchers and film-makers first mentioned by Lennart Meri and by one of the most famous philosophers of the latest time Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov from the stage of the Moscow House of Cinema on May 26, 1987. In summer of the same year in the resort Baltic town of Parnu the Secretary of Estonian Filmmaking Union Mark Soosaar organized the first USSR festival of visual anthropology.

|

Pic. 17. Vyacheslav V.Ivanov

For the majority of Russian participants of the festival it became a surprise that many foreign film-makers not just tried to recapture the atmosphere of existence of unknown human communities, moreover, they set a mission to help the spectator enter into the screen life of those other, strange worlds. In the majority of movies the canon of promotional and propagandist function of the documental cinematography, so usual in Russia, was totally defied. To replace it there was offered a new algorithm of screen reality perception through self-exercised analysis and receiving of aesthetic impressions from emotional contact with another life, shown truly and with dominance of ethical responsibility of the film-makers towards the depicted life and the spectators.

For my friend, associate and author of an article Leonid Filimonov back in those years the festival became the first and the most important source of introduction to the visual anthropology: with its representatives, ideas, information and, most important, with the movies. Already in 1989 we started building up a video library with the help of which we prepared the first in Russia special course of study, and during ten years basing on that course of study we were teaching classes on the Faculty of History at the Moscow State University.

|

Pic. 18. Leonid Filimonov

But the core event that had defined our activities in the next quarter of a century was an invitation to participate as graduate associates in the first school for the low-numbered peoples of Siberia. The organizer and manager was the chairman of the Commission of visual anthropology by the International Union of anthropological and ethnological sciences, the professor of Melbourne University, one of the students of Margaret Mead – Asen Balikci. He was supported by an American anthropologist Mark Badger [Danilko 2017, 95-112].

|

Pic. 19. Asen Balikci and Mark Badger

It was easy for us to conceive the ideas and methodology of visual anthropology. Our previous professional experience was related with the only university cathedra of scientific cinematography and photography in the whole Soviet Union. We worked in a technically well-equipped laboratory which conducted research in different fields set by different faculties of the Moscow State University by means of cinematography.

Even though by that time the cathedra ceased to exist, the film laboratory and a huge scientific film archive were preserved.

The breadth of knowledge of the Kazym workshop professors, their level of discourse, teaching methods, humanitarian ideas, expertise, charm and benevolence of Asen Balikci – all that inspired us to organize on basis of the film laboratory a Visual Anthropology Centre at the Moscow State University. With participation of pupils and volunteers, specialists from different organizations and scientific spheres we established works on a wide range of areas.

|

Pic. 20. Group photo Center of Visual Anthropology at the Lomonosov Moscow State University – 1995

The main challenge up till now is to recollect and preserve audio-visual materials and to create a state-of-the-art multimedia archive. Its creation at the start was supported by participation in the program of INTAS together with a Senior Archivist, Professor Vladimir Magidov and Rolf Husmann, a member of Institute of Scientific Film Knowledge and Media, Goettingen, Germany. Currently the laboratory keeps designing and annotating movies on the topic of “Visual Anthropology of the World”. The Archive, listing over 700 names, is being constantly referred to by researchers and university and school professors.

The Centre’s publishing activity is represented by 8 symposiums and translations of foreign literature, its proper theoretical research in the field of visual anthropology is represented in more than 100 publications.

On the basis of the first Russian original special course approved by the Moscow State University there were later on held:

- travelling schools and workshops in several cities of Russia;

- since 2016 there exists a master course entitled “Visual Anthropology of Childhood” in the Moscow Pedagogical University.

Starting 1993 the Centre constantly initiates and conducts seminars and classes of visual anthropology at conferences (including Russian anthropologists’ congresses), which purpose is to discuss the results of application by university researchers the audio-visual means during expedition work.

|

Pic. 21. Norwegian-Russian seminar in the Lomonosov Moscow State University in 2015

In 1998 the Moscow State University Centre, together with Andrey Golovnev’s group organized the first Russian festival of anthropological films in Salekhard city. The festival was presided by a famous philosopher, the director of Russian academic Institute for Human sciences Oleg Genisaretsky.

|

Pic. 22. Salekhard 98 - festival poster

In an effort to create a Moscow ground for meeting of western and Russian visual anthropologists, the Moscow State University Centre organized and conducted seven Moscow international festivals of visual anthropology named Cameramediator between 2002 and 2017. A distinguishing feature of an information festival was a student debut competition, a scientific conference, topical workshops and discussion groups.

Professional cinematography preparation, previous working experience in research filmmaking in the university laboratory and becoming familiar with the possibilities of portable video cameras and computer technologies allowed to elaborate in pretty short time an original method of shooting named “concordant camera” based on which they started to make research video-documenting of traditional culture. A distinctive aspect of the original method is from one side a strictly documentary and at the same time aesthetic approach to showing the events, and from the other side the awareness of moral responsibility towards the culture and its representatives. It is a kind of “flahvertism”: an effort of synthesize the approaches of the two founders of the documentary cinema – Flaherty and Vertov [Aleksandrov 1998, 62-68].

The strong and weak points of the new approach are the priority of interests of the culture demonstrated to the information recipients. The work success is to a large extent defined by finding a balance between the parts of the communication process. The problem of ethical responsibility can be partly solved by restriction of access to the working materials aimed for scientific analysis, as well as by sticking to ethical norms in films for wide audience representing research documents about cultural communities.

The first festival film, made according to the new principles in 1992 by Leonid Filimonov together with a famous folklore specialist Serafima Nikitina, was Molokan Spiritual Singing. Further on the work was done on the Old-Rite topic in expeditions organized by the leading researchers: first by the Moscow State University historians Irina Pozdeeva and Elena Ageeva, then by anthropologist of Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences Elena Danilko.

|

Pic. 23. A shot from the film Molokan Spiritual Singing

Presently the archive of traditional culture boasts about 300 hours of video films, basing on which there have been created over 20 films frequently demonstrated at Russian and foreign conferences and festivals [Aleksandrov 2003, 95-97].

The wide colour palette of contemporary Russian visual anthropology is far from being limited to the activity of the Moscow State University Centre alone.

In Moscow, besides Moscow State University, there are working groups from Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography, Russian State University for the Humanities, Moscow State Pedagogical University, and the Higher School of Economics, effecting research and educational complex activities. No less actively are working research groups in other cities.

Back in 1992 an anthropologist Andrey Golovnev opened his saga about the Nenets – the indigenous people of the North – with the films Tatva’s way and Gods of Yamal. With these and posterior works, as well as the focus of the Russian Anthropological Film Festival (RFAF), he persistently defends the priority of the popular science genre in the ethnographical cinema [Golovnev А. V. 2011, 83-91].

|

Pic. 24. A shot from the film Tatva’s Way

Another promising anthropology film director of the present time, Ivan Golovnev, sticks to a similar theoretical position [Golovnev I. A. 2016, 83-98]. At the same time, in his works the film director often steps over the usual bounds of the popular-science genre. In his movies Little Katerina and Old Man Peter it is impossible not to notice how attentively and tactfully the film-maker knows to enter the characters’ lives, giving them the opportunity of communicating with the spectators on their own behalves.

|

Pic. 25. A shot from the film Old man Peter

A number of films about the Chukchi by another talented young film-maker Aleksey Vakhrushev, working at the laboratory of Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences created some time ago by Aleksandr Oskin, is continued by a film The Tundra Book: A Tale of Vukvukai, the Little Rock.

|

Pic. 26. A shot from the film The Tundra Book

In spite of the information technology progress and the absence of global ideological censure, the popularization supporters in the films of ethnographical topic keep holding strong positions. The freedom of form, typical for popular science genre, contributes to that, as well as the reliance on the steady perception of the audience which is being strongly supported by the television, skilfully combining commercial entertainment with propaganda tasks.

A kind of alternative to this trend is provided by separate specialists and research groups shooting films in ethnographical expeditions, working in the universities of Samara, Novosibirsk, Izhevsk, Perm, Ulyanovsk, Tomsk and other cities. These video materials often contain unique information. However, these materials are never shown to represent the research that could be available for the wide audience or introduced at festivals, as they do not meet the requirements of the aesthetic expression. The audio-visual information created by such films is normally used to illustrate the presentations proper and in teaching, and as the result are available for a relatively narrow circle of specialists.

Along with universities, local folk museums and natural history museums are becoming the organizations not just using the documentary films for education purposes, but accumulating collections of ethnographical and audio-visual information more and more frequently. Their undoubted leader is the research institute and museum of the Kunstkamera in Saint-Petersburg, where an expert in the Oriental history, culture and Islam, Efim Rezvan, for many years has been making media projects, and organizing representative exhibitions basing on his proper research materials.

Although for the last quarter of a century the Russian visual anthropology has reached some success, it should be acknowledged, that the main contribution into intercultural communication was still made by the cinema and the television. Same as before, a professional documentary cinematography represents a great volume of information, which is available and may be used by specialists of various disciplines.

It becomes obvious that the main spheres of application of ideas, methodology and materials of visual anthropology, at least at the present stage, are scientific and education spheres. And here many problems should be solved. For a country with a great number of nationalities and religious confessions there are too few university professors and far less secondary schools that are familiar with visual anthropology and are ready to use its possibilities. Even researchers such as anthropologists, ethnographers, sociologists, and cultural specialists – rarely apply this new method of information and unusual tools in their work. Up till now there has not been bridged the gap in knowledge of the massive of foreign literature. There are few introduction special courses, residential schools and workshops, and the first professional master courses teaching special skills of work with audio-visual information are just starting to emerge.

The problem of cinematography specialist training of academic, university and museum staff conducting their own visual-anthropology researches is one of the most important.

However, the direct borrowing of formed and popular stylistic devices of the documentary cinematography would be wrong. Specific tasks of visual anthropology supposing organic combination of contemporary scientific knowledge and human overview, of ethics and corresponding with new tasks of aesthetics require totally different approaches.

Of a certain help in solving this problem could be studying of experience of some festivals of documentary films, which are supporting the documentary film makers, even though they weren’t specialized on ethnography topic, but they would study the language and methodology of research cinematography. In this new stylistics of non-fiction there work, including, graduates of Marina Razbezhkina’s studio, heading the movement of young film directors [Hicks 2017].

A pioneer of this streamline and predecessor of Moscow festivals Docker and Artdocfest is the festival Flahertiana which was organized by Pavel Pechenkin in Perm in 1995. Having set professional cinematographic challenges in the beginning of his career, the talented film director and producer has been recently making a lot of efforts for introduction of documentary films into media education system [Pechenkin 2014].

Such motivation coincides with disciplinary interests of visual anthropologists, whose main task at the present stage is to organize master courses in several universities.

Rethinking of the documentary cinematography experience, the basis created by enthusiasts of the new discipline for the last quarter of a century, the progress of information technology which is becoming more and more available, and, what’s more important, the necessity of taking into account interests of different national and religious communities - all this inevitably makes actual the task of development of intercultural communication basing on humanitarian principles of visual anthropology.

Aleksandrov E.V. 1998, "Sozvuchnaja kamera" v "dialoge kul'tur", Material basis of culture. To the first festival of visual anthropology in Russia, Moscow: Russian State Library, 2: 62-68.

Aleksandrov E.V. 2003, Opyt rassmotrenija teoreticheskih i metodologicheskih problem vizual'noj antropologii,Moscow: Penaty.

Aleksandrov E.V. et. al. 2007, Forum Vizual'naya antropologiya, «Forum for Anthropology and Culture: Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera) Russian Academy of Sciences», Saint-Petersburg, 7: 6-108.

Aleksandrov E.V. 2017, Centrostremitel'nyj vektor v bezgranich'i vizual'noj antropologii, «Siberian historical research Tomsk State University», Tomsk, 3: 11-28.

Arzyutov D. 2016, Etnograf s kinokameroj v rukah: Prokof'evy i nachalo vizual'noj antropologii samodijcev, «Forum for Anthropology and Culture: Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera) Russian Academy of Sciences», Saint-Petersburg, 29: 187-219.

Baklin N.V, Kalashnikov A.G 2003, Pervye shagi nauchnogo kino v Rossii (Publikatsiya A.S.Deryabina, kommentarii S.V.Skovorodnikovoj pri uchastii A.S.Deryabina, «Kinovedcheskie zapiski», Moscow: Eisenstein Centre, 64: 184-189.

Batalin V.N., Malysheva G.E. 2011, Istorija Rossijskogo gosudarstvennogo arhiva kinofotodokumentov. 1926–1966 g. , Saint-Petersburg: Liki Rossii.

Chuyko S. 2017, Tropoj Sakari Pjalsi, «Gazeta Krajnij Sever», Anadyr, 13/07.

Czeczot-Gawrak Z. 1995, Bolesław Matuszewski, filozof i pionier dokumentu filmowego. — W: Bolesław Matuszewski. Nowe źródło historii. Ożywiona fotografia, czym jest, czym byc powinna, Warszawa: Filmoteka Narodowa.

Danilko E.S. 2017, Kazymskij perevorot k istorii pervogo vizual'no-antropologicheskogo proekta v Rossii, «Siberian historical research», Tomsk State University, 3: 95-112.

Deryabin A. 1995, Vertov i Erofeev: Dve vetvi dokumentalistiki, «Flahertiana Festival katalog», Perm', Novyj Kurs Film Studio: 65–71.

Deryabin A. 1999, O fil'makh-puteshestviiakh i Aleksandre Litvinove, «Vestnik Zelenoe spasenie», Almaty: Germes, 11: 14-23.

Deryabin A. 2001, Nasha psihologiya i ih psihologiya— sovershenno raznye veschi. «Afganistan» Vladimira Erofeeva i sovetsky kul'turfil'm dvadtsatyh godov, «Kinovedcheskie zapiski», Moscow, Jejzenshtejn-centr, 54: 53-70.

Gibert G. G., Nyrkova D. A. 2016, Kavkaz v dorevoljucionnom dokumental'nom kino, Krasnodar: Nasledie vekov.

Glebova N. 2016, Tolstoj v dokumental'noy kinohronike, «Narodnoe slovo», Lipetsk Region, settlement Lev Tolstoi, 12.12, https://narodnoeslovo.ru/?p=7618

Golovnev A. V. 2011, Antropologija plus kino, «Kul'tura i iskusstvo» NB-Media, Moscow, 1: 83-91.

Golovneva E. V., Golovnev I. A. 2016, Vizualizaciya regiona sredstvami kinematografa (na primere «Kinoatlasa SSSR»), «Izvestia. Ural Federal University Journal», Yekaterinburg, series 1, 22 (3): 146-151.

Golovnev I. A. 2016, “Lesnye lyudi” – fenomen sovetskogo etnograficheskogo kino, «Etnograficheskoe obozrenie», Moscow: Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology Russian Academy of Sciences’, 2: 83-98.

Hicks J. 2017, Marina Razbezhkina: Five Interdictions and the Zone of the Snake, «KinoKultura», Bristol 55, http://www.kinokultura.com/2017/55-hicks.shtml.

Ishevskaja S., Viren D. 2007, Boleslav Matuszewski . Zhivaja fotografija: chem ona javljaetsja i chem dolzhna stat'. Perevodchik Grigorij Boltyansky. Publikacija, Predislovie i kommentarii Svetlany Ishevskoj i Denisa Virena, «Kinovedcheskie zapiski», Moscow: Eisenstein Centre, 83: 128-161.

Jacoby J. 1995, Znałem Bolesława Matuszewskiego. W: Bolesław Matuszewski. Nowe źródło historii. Ożywiona fotografia, czym jest, czym byc powinna. Filmoteka Narodowa, «National Film Archive», Warsaw: 37-42.

Kubeev B.V. 1958, Nauchnaja kinodokumentacija , vypolnennaja v vuzah v 1945-1957 gg ., Moscow: Sovetskaya nauka.

Lebedev N.A. 1947, Ocherk istorii kino SSSR: Nemoe kino, Moscow: Goskinoizdat.

Lemberg A. 1976, Druzhba, ispytannaya desyatiletiyami – V: Dziga Vertov v vospominaniyah sovremennikov, Moscow: Iskusstvo: 79–85.

Macza I. 1933, Rossijskaya associaciya proletarskih hudozhnikov v zhurnale «Za proletarskoe iskusstvo» 1931, «Sovetskoe iskusstvo za 15 let», № 5, Moscow-Leningrad: OGIZ-IZOGIZ.

Magidov V.M. 1999, Itogi kinematograficheskoj i nauchnoj dejatel'nosti B.Matushevskogo v Rossii, «Kinovedcheskie zapiski», Moscow: Jejzenshtejn-centr, 43: 268-280.

Malevich K. 1933. Programma «levyh» bespredmetnikov v zhurnale «Izobrazitel'noe iskusstvo», № 1, 1919 g. - Sovetskoe iskusstvo za 15 let, Moscow-Leningrad: OGIZ-IZOGIZ.

Medvedev M. 2014, Dziga Vertov. Lovets zvukov, ili Doktor Frankenshtein, «Chastnyj korrespondent»,

Moscow 02.01 ww.chaskor.ru/article/2_yanvaryadziga_vertov_lovets_zvukov_ili_doktor_frankenshtejn

Mislavskij V.N. 2006,Alfred Fedetsky: K biografii pervogo rossijskogo kinooperatora, «Kinovedcheskie zapiski», Moscow: Eisenstein Centre, 77: 163–213.

Pechenkin P. 2014, Esli ty zhivesh' v Permi i hochesh' zanimat'sya kino, net neobkhodimosti uezzhat' v Moskvu, «Entciklopediya dokumental'nogo kino», Moscow: Gil'diya neigrovogo kino i televideniya, 11.11. // http://rgdoc.ru/materials/intervyu/13041-pavel-pechenkin-esli-ty-zhivesh-v-permi-i-khochesh-zanimatsya-kino-net-neobkhodimosti-uezzhat-v-mosk/

Pink S. 2006, The Future of Visual Anthropology: Engaging the Senses, London: Routledge.

Roshal L. 1982, Dziga Vertov, Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Sarkisova O. 2017, Screening Soviet Nationalities: Kulturfilms from the Far North to Central Asia, London: I. B. Tauris.

Shnejderov V. 1964, Fil'my-puteshestviya – V Nauchno-populjarny fil'm. Vyp 2, Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Shnejderov V. 1970, Fil'my-puteshestviya – V Kino i nauka. Vyp. 3, Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Shub E. 1972, Zhizn' moya – kinematograf, Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Vertov D. 1966, Statyi. Dnevniki. Zamysly, Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Vishnevsky V.E. 1996, Dokumental'nye fil'my dorevoljucionnoy Rossii: 1907–1916, Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Yutkevich S.I. 1966, Kinoslovar' v dvuh tomah, Tom I, Moscow: Sovetskaya entsiklopediya.

[1] Polish researchers have recently remembered the unheralded expert and theorist of cinematograph [Jacoby 1995, 37-42; Czeczot-Gawrak 1995, 11-12]. In Russia Vladimir Magidov issued the most detailed work, where, in particular, he notes that back in the 30th-40th of the 20th century the heritage of B.Matuszewski was studied by another researcher – Grigory Boltyansky [Magidov 1999, 268-280]. In a later article there was published and commented a manuscript translation from French of two books by B.Matuszewski made by G.Boltyansky in 1940 [Ishevskaja, Viren 2007, 128-161].

[2] These materials have come down to the present time in abundance and, after a long ban period, have come available anew. Naturally, they may only to a certain degree of convention be classified as visual anthropology: they have been conducted by the court photographer under constant control and with a high degree of self-censorship. However, such a solid and diverse, in terms of narrative, film chronicle, which had been being shot for a decade and a half, could fairly become a material for a contemporary anthropological research. In 1992 film directors Viktor Semenyuk and Viktor Belyakov in their movie House of the Romanovs and Nikolai Obukhovich in his film Une foule de princesses blanches tried to offer some answers to the concerns regarding the destiny of the tragically killed family of the last Russian Emperor, which bothered the society after the fall of the USSR.